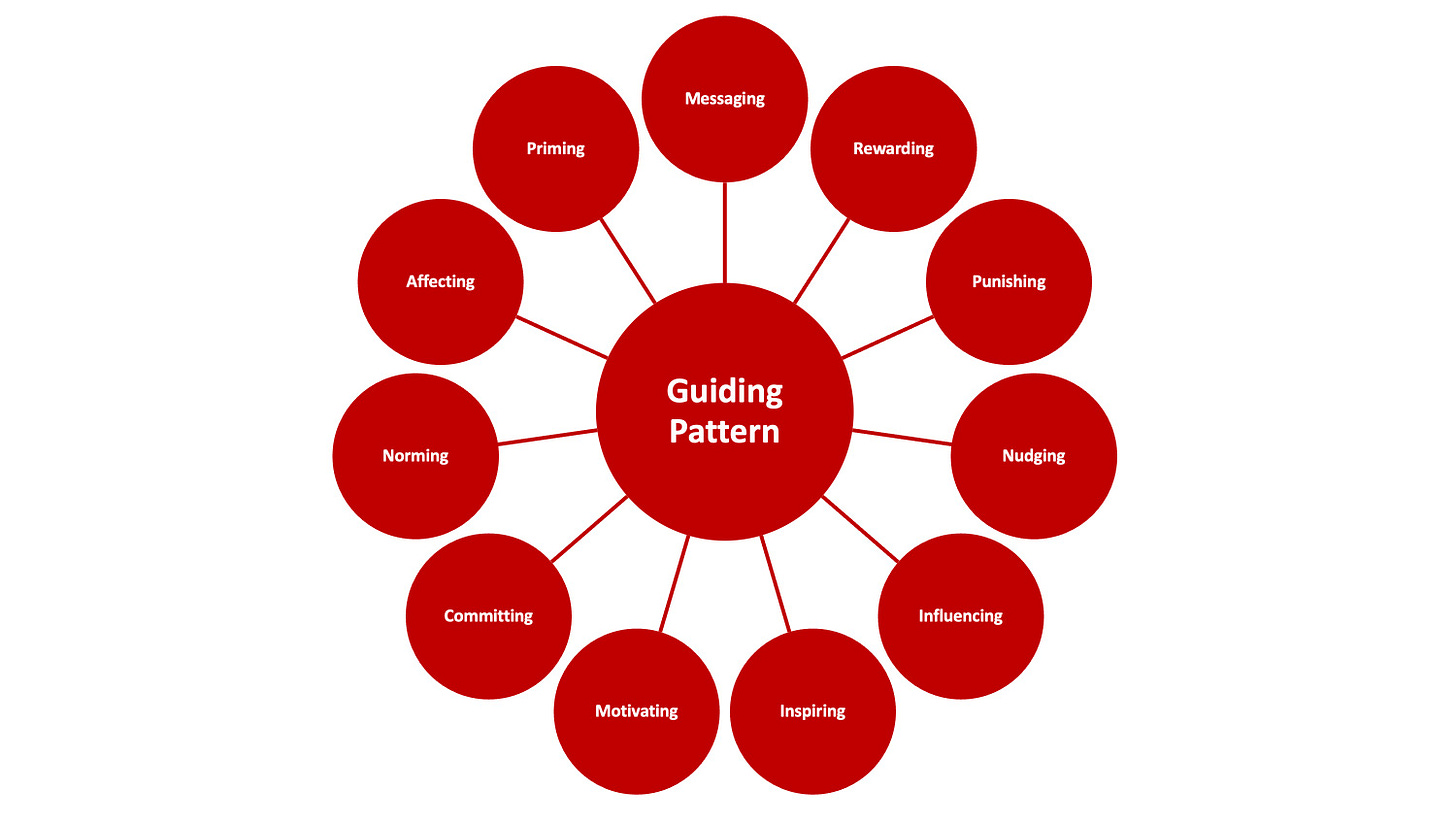

Guiding Pattern

Supporting the strategic design process without imposing control or manipulation

Research suggests that learning by trial and error, observing how others behave and modelling our behaviour on what we see around us provide more effective and more promising avenues for changing behaviours than information and awareness campaigns.

Tim Jackson1

Challenge: How can you apply behavioural science to support a living systems approach to transformation?

Cluster: Enriching Practice Patterns

Type: Essential Practice Pattern nested within the Design Cycles Pattern

Purpose

The Guiding Pattern supports transformation with application of behavioural science, while avoiding use of coercive and manipulative behaviourist tools and methods by situating such methods within a living systems approach.

Pattern Description

The Guiding Pattern is positioned to support and enrich the Design Cycles Pattern. It places behavioural science in an appropriate context in transformation - in service to the transformation rather than directing it.

Behaviour change and behavioural science is important because it can help us understand people and change and to look for patterns of behaviour in a social entity.

A common assumption in a behaviourist approach is that if carried out over enough individuals, behaviour change will bring about social and cultural change. However, conventional behaviour change methods used by governments, policy makers and organisations are frequently ineffective, and mostly work on single-issue change.

Behaviour change for sustainability is more complex, as transformation is multi-faceted and multi-directional: it proves even more difficult to sustain than single-issue methods.

Yet, these methods are the pathway of choice for change agents in initiating change: generally applied in a linear, mechanistic fashion usually aimed at the individual on specific single-change issues. They can range from the simplistic to manipulative; from controlling to coercive; and if used as the primary method, can be dangerous and counterproductive. These patterns are incompatible with sustaining a transformation in a healthy human system.

A nuanced view of behavioural science is applied in Living Systems Practice: one which explores the idea of human behaviour as a complex ecological system with many competing pressures. Ecological models have had success, have been supported by theoretical research and bring together individual, interpersonal and community perspectives.

Within a Living Systems Practice approach, behavioural science provides useful insights on people and change when embedded in a complexity-based approach.

Elemental Patterns

Messaging: Communicating to participants and stakeholders is an important contribution to transformation activity. The visions and pathways to transformation must be well understood by participants early in the process, assisted by knowledge exchange and sharing of experience throughout the process. A central and common practice in communication is the use of messaging, usually limited to three or four “key” messages: keep it simple in order for people to take the message on board. This is far too simplistic for a complexity approach where change proceeds in a multiplicity of ways, for a mulitplicity of outcomes, where multiple forms of messaging can help reinforce experiential learning across the social entity.

Rewarding: The use of rewards is central to behaviourist methods, although rewards typically lose their impact in the short term, because they soon become normalised and less effective. Rewards are often overused, leading change down a counterproductive transactional path; so they should be used judiciously so as to not create expectations of reward for every step taken in change. Any specific rewards should focus on groups rather than individuals, and only in relation to activities and outcomes that lead to greater connection, coherence and system activation.

Punishing: Punishing unfavourable behaviour, like rewarding, is commonly used to manage behaviour, yet is also counterproductive in a sustainability transformation, as it will create resistance rather than cooperation. Of course, constraints can be applied to lead to better behavioural patterns and to prevent destructive behaviours, but alignment of the social system through interaction, collaboration and other system effects will be more effective. Having an unsustainable world is punishment enough.

Nudging: The concept of Nudging - or “choice architecture” - emerged in the last fifteen years as a subtle behaviour change method in public policy design. Application of the method is by limiting available options, leading people to adopt behaviours aligned with the preferred policy. Nudging has proven effective in many situations, and is still a popular approach in public behaviour change programs. Nudging has a downside: in spite of the subtle nature of nudging people towards desirable behaviour patterns, over-use and unscupulous application in some contexts have resulted in it being identified in the public mind as a subversive form of manipulation. Use of nudging in sustainability transformations should therefore be applied carefully in a way to assist other holistic adaptive systemic processes.

Influencing: There are influencers in real life and “Influencers” in popular culture, and in this Elemental Pattern, the focus is on influence that occurs naturally in real life - in human systems, not the manufactured, self-centred and shallow type common in social media. Anyone in a human system can influence change in their personal networks, whether directly or platformed. Understanding how members of a social entity behave and influence their local networks is important for framing change, as it will help identify and respond to negative influencers and identify people who have capacity to positively live the change and model it to peers.

Inspiring: True inspiration that lights up a transformation can come from anywhere and through any phenomenon: people, events, case studies, and stories, and within or beyond a social entity. Regularly supporting a transformation with case studies, personal stories and exposure to experiences can inspire people to know that change is possible in their social entity. This approach to inspiring people is an effective contribution to growing sustainability culture.

Motivating: Motivated leaders, groups and people are critical for sustainaing transformation efforts. Human energy can dissipate over the course of a transformation, so motivating people when things become difficult is a critical guiding art. Motivation is also a critical dimension of learning, because of its links to system feedback and creating culture. Motivation is intrinsic or extrinsic - from personal interest or outside influence - and is more effective when change can appeal to people’s need fr self-determination and self-actualisation.

Committing: Asking people to make voluntary, public and personal commitments to a change process is a common engagement approach. The theory is that people that make public pledges to a behaviour change will be more likely. In practice, such stand-alone efforts can work in the short term, but commitments are more effective and sustainable when part of an overall systems approach, where other change methods are used in the practice context. Commitments should only be applied in change activities with potential significant impact, because while there is good evidence that commitments are effective in engaging people, there is limited evidence that they lead to sustained change.

Norming: Norming is an activity that draws on participants personal and social norms as a means to connect those norms to the purpose of change. This can engage participants more deeply, by making the change more salient - more relevant. If people can see that changes are congruent with their personal and social norms, then such changes can then be more readily accepted and they can maintained through occasional prompts, reminders and the influencing activities of peers and leaders.

Affecting: Affect is a domain of psychology in addition to behavioural and cognitive domains. Based on feeling, emotion, attachment, sentiment, temperament and disposition, it can have a significant influence on the pace and effectiveness of change. Affective factors may be at play when people resist change, and will certainly need to be activated as part of maintaining participants enthusiasm and commitment to change. Affect displays from participants can act as a guide to how change is received by participants and can also signal underlying or emergent issues as new patterns in the practice context.

Priming: Priming is a form of interpersonal and social interaction where leaders and advocates of change prepare a stimulus to open up the change process through a range of media and interventions, so that individual participants are more ready to participate in change activities. In a positive sense, this can be part of a gradual approach to engagement and participation, and should be used wisely, and at ther service of holistic outcomes. However, if not carefully applied, priming can be a pre-cursor to misleading, manipulative and coercive actions by the leadership of a social entity - effectively priming is part of a power play. If applied in this way, outcomes will only be sustainaed through command-and-control approaches contrary to a Living Systems approach: this should be avoided.

Atlas Navigation

Go to the Elemental Patterns within the Guiding Pattern:

Messaging Rewarding Punishing Nudging Influencing Inspiring Motivating Committing Norming Affecting Priming

Go to the Enabling Pattern within the Enriching Patterns Cluster

Go to the Conviviality Pattern within the Enriching Patterns Cluster

Version

Version 1.0 - 2 Jun 2024

Version 1.1 - 23 May 2025

Version 1.2 - 15 July 2025

Jackson, T. (2004). Motivating Sustainable Consumption. A Review of Evidence on Consumer Behaviour and Behavioural Change. A Report to the Sustainable Development Research Network. Guildford UK: Centre For Environmental Strategy, University of Surrey.