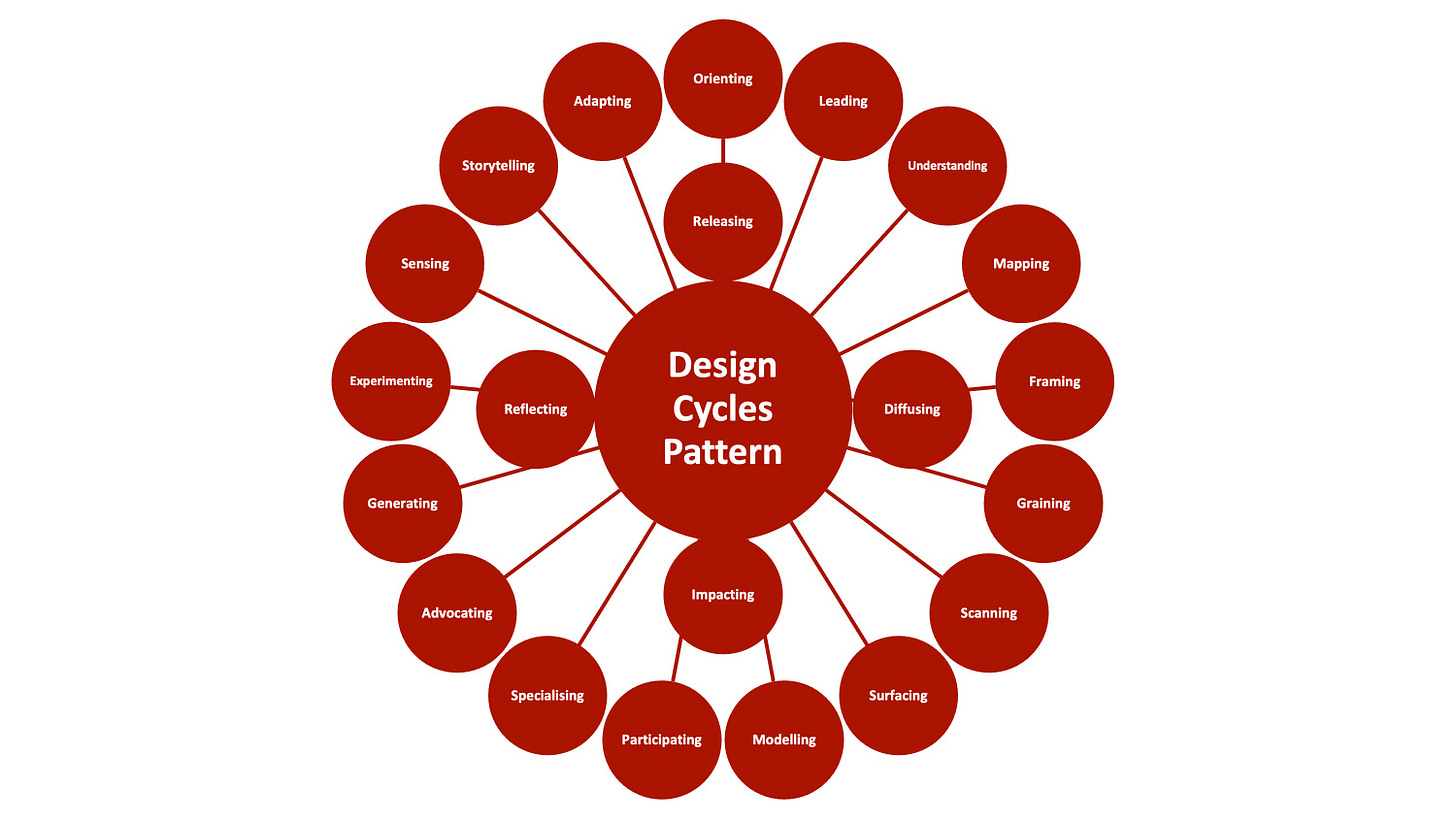

Design Cycles Pattern

Purposefully shifting a system to a preferred system state through creativity, participation and emergent patterns

Design, if it is to be ecologically responsible and socially responsive, must be revolutionary and radical.

Victor Papanek1

Challenge: How might you create the change the world needs in your organization, network, community, group or team within ecosystem limits and planetary boundaries?

Cluster: Transforming Practice Patterns

Type: Essential Practice Pattern nested within the Phase Pattern

Purpose

The Design Cycles Pattern facilitates a whole-system transformation through a design-led process.

Pattern Description

Nested within the Phase Pattern, this Pattern is suitable for a social entity of any scale with its the Elemental Patterns being action-oriented and working in concert with each other in a dynamic way.

The Design Cycle Elements are based on a creative cycle, and they are focussed on what is needed to design in the practice context. The Design Cycles Pattern is applied through each of the Phase Patterns as a cyclic, spiralling trajectory.

The Design Cycles Pattern is scale-free in the sense that the process of change incorporates the identified elements, but the priority or weighting of elements is left to practitioners and participants to experiment with. Likewise, there is flexibility in the ordering of activity.

Start with the Orienting Pattern then proceed around the Pattern’s circle. Be aware that there are other dynamics at play such that you will frequently re-consider Elements already initiated, as more knowledge about the design and the design context emerges. There is some linearity with these Elemental Patterns in as much as any design idea will not be released into the wild until it has undergone some development; the context understood; framing and graining has been initiated and so on.

Thus each Elemental Pattern can be chosen, prioritized, and applied, until the Phase outcome has been designed, tested and released into the wild.

You can also start where you are – you may already have an untested strategy ready for implementation, and the cycle can commence from there, through a review and refinement process that will lead you to ultimately consider all of the Elemental Patterns in some way before moving to the next Phase. Consider this a safe-fail experimentation. The worst that can happen is that you have moved the process on prematurely, and you will have to return to an Elemental Pattern to do deeper work.

The Design Cycles Pattern also contains to three Nested Patterns - the Enabling Pattern, Guiding Pattern and Conviviality Pattern. These Patterns are also in the Enriching Patterns Cluster, as they help to enrich the design process.

Elemental Patterns

Orienting: This Elemental Pattern embeds sustainability principles as deeply into the formal social entity structure and its codified processes as possible. Thus, the importance of any given structure over any other is diminished, allowing other elements in the model to have increased effect for change. As the other Design Cycles Pattern elements are activated, they can foster sustainability through emerging systems, rather than defined structures.

Cultural change for sustainability begins with articulating a vision of a preferred culture: that is, the set of norms, values, attitudes and behaviours that need to be expressed by members of an organization to fulfill a sustainability vision. In principle, if a culture of sustainability has been embedded, people will demonstrate that culture in many diverse ways: through their use of language; how they approach challenges; who they connect with and support; whether they actively facilitate sustainability actions; and through their levels of motivation to learn more about sustainability and apply what they have learned.

Leading: Two forms of leadership are required: the conventional version, with leaders gaining formal authority through formal structures; and distributed leadership, where individuals, usually self-selecting, at all layers and scales behave as natural, informal leaders. Both are necessary for an emergence-based approach, as most people are used to leadership within formal authority structures, and will always look to their formal leaders. However, people respond well to natural leaders. Distributed leadership can amplify sustainability principles in places where formal leadership is less effective in fostering change. Understanding the informal leaders in an organization – who they are and their values, behaviours and motivations – are critical, as they can also be the people blocking imposed change if they don’t agree with it or believe in it. Having such influencers identified and gradually aligned is a critical leadership task.

Understanding: Understanding the context through primary and secondary research of the organization – its systems, participants and stakeholders. Practitioners should challenge assumed knowledge and be good at asking questions to understand the dimensions of the design context. Resist conventional surveys – they usually only state the obvious. Never take information on face value – it may be a symptom of something else or a weak but potentially significant signal. Triangulate amongst sources for consistency or contrast. Create questions as responses to narratives.

Mapping: This Pattern involves identifying and mapping patterns of behaviour in the practice context: Who and what is involved? How do they connect and what are the dynamics of the relationships? Where are the attractors? Phase changes? Tipping points? Where do things flow, where is flow blocked? It also involves categorizing: What type of system are you working in? Are multiple complexity categories at play? Is the predominant practice domain technological, institutional, social, knowledge, ecological? How can organizing information into themes deepen understanding? Avoid applying the wrong tools in the predominant domains: different domains and different thematic areas may require different approaches.

Sustainability practitioners must develop skills in detecting patterns of behaviour in the system via mapping processes. In complexity theory, consistent patterns of behaviour are indicative of an attractor: an emergent form of behaviour where stability is demonstrated. Such stability can be around sustainability activity, in which case it is evidence of the culture change process, or attractors can obstruct the change because of entrenched behaviours.

Framing: Framing involves the setting of contingent boundaries to the practice context, by probing new knowledge to emerge from Mapping, and by contingent decision-making about the system boundary. Framing should not be a fixed activity – ideally a number of contingent frames should be held and experimented with early in the process and should be revisited as feedback builds. In highly complex practice contexts, practitioners should settle on a problem frame as a highly contingent position and adjust as the work proceeds.

Graining: While Framing practice contexts is a common task in DT and other business and innovation methodologies, Graining the problem context is not! Graining will help practitioners decide the level of detail appropriate to the degree and complexity of change, especially for commencing the Activating Phase. Subsequent Phase cycles present opportunities to adjust the Graining with the general Framing. Decisions about Graining can be adapted as confidence in the change process develops.

Scanning: Here, Scanning means “scanning the future” to enable the design of the transformation. The mere act of designing and creating means decisions are being made about shaping a possible future: having a sense of possible futures at the outset is an important role, particularly at the Activating Phase as well as the other three Phases. This is not about predicting the future – it is about uncovering pathways to futures that can be sustained. Many tools can be applied, such as scenarios, backcasting, roadmapping and horizons, but it is important to choose based on degree of uncertainty of the practice context.

Surfacing: In complex systems, not all systems dynamics, behaviours and emerging patterns are visible to participants. Bringing such phenomena “to the surface” is an important activity, but this cannot be done through direct questions, surveys and activities which work through the conscious mind, generally identifying the obvious. Seeking out the unknown, especially weak signals from the external environment (not to be confused with “trends”) is highly significant for transformation. Surfacing is best done through narrative methods, where stories shared can help to uncover issues that people are not conscious of. It is also important to understand the hidden networks of the organization – the one’s not shown on any organization chart – their location in the system and their degree of connection, hence their existing influence and potential for Pulsing new ideas and information.

Modelling: Participants model desired behaviours and practices associated with the change vision. Leaders, decision-makers and champions model desired sustainability behaviours at every opportunity. Encourage all participants to demonstrate sustainable behaviour at their scale of activity. Recognise and reward behaviour change achievements publicly. Include changed behaviours in the on-going organization narrative; and incorporate any emergent innovative sustainability behaviour in policy design, role descriptions and expressions of preferred sustainability culture. Note that in a complexity context, behaviourist approaches may be appropriate, but they are at the service of a complexity approach.

Participating: All aspects of the transformation process must engage as many people across the organization as possible through meaningful collaboration and participation with impact, avoiding dominance from the top down. This Pattern prioritizes collaboration, participation and deep engagement. Thus, the real work of transformation is led by a diversity of people as change agents and experts in their own organization – it can’t be imposed by external agents or consultants. Without full participation and collaboration across the organizational ecosystem, the process becomes a top-down or outside-in process and for complex change, that approach is only a part of what’s needed. Deep engagement which enables bottom up and inside out participation is more holistic.

Specialising: Much sustainability work is project-based and situated in complicated space where deep knowledge and experience of an activity area requires the contributions of technical experts. Such expertise can involve application of codified knowledge and design methodologies, such as in engineering, planning and architectural, urban or product design.

In conventional sustainability practice, the expert or specialist usually leads the change effort, and thus such change efforts may often be framed according to the bias and interests of the specialist. Many specialists do not have a generalist capacity or experience to connect their efforts to the efforts of other specialists and activities in an organization. In this Elemental Pattern, the role of the specialist is just as valued as it is in mainstream practice, yet it becomes more connected to other perspectives and contributes to reduction of a silo mentality, depending on the degree of complexity of the practice setting.

Specialist roles can add greater value to a sustainability activity than occurs in conventional practice by incorporating knowledge gleaned from other parts of the organization. Caution is required because experts can exert a substantial amount of influence over the direction and scope of decision-making. If specialist activity loses connection to the whole, then the synergies and emergent possibilities of a connected organization can be lost to a sustainability transformation activity. Expertise applied at key system points, with guiding decision-making from generalist practitioners, is more appropriate and connects better with the organization as a living system.

Advocating: All transformation work needs advocates, or champions, to hold the spirit behind the change, and promote it or defend it as necessary. Unlike the usual use of champions in change, in Living Systems Pratice champions act within stimulated and connected systems, and with more understanding of the system and its leverage points. Advocates are most important when the energy for change in the system runs low.

Generating: Participants contribute to generating ideas and creating pathways to change – such strategic design is distributed across the organization. This Elemental Pattern can traverse complicated, complex and chaotic space. This is where real decisions must be made: transforming the unknown into the known. While much design emerges from specialist activity, there is an implied trust that the designer understands the local context and will propose appropriate solutions. Thus, creation of new ideas to address sustainability challenges must go beyond the expert and incorporate local contexts and their local emergent patterns and knowledge. Creating new ways of doing things as well as designing supporting processes is an on-going challenge in every Phase. Design never stops!

Experimenting: All work is permanently “beta”, and ideas and processes should be tested in safe-fail experiments in smaller-scale. Participants will have their own hypotheses about the transformation, so the Experimenting Pattern enables many different hypotheses to be tested. Rather than mapping a course of action with a high probability of failure or high level of impact in the event of failure, a “safe-fail” experiment may help to chart a way forward. Such experiments should be designed with the purpose of maximizing knowledge about the nature of the complexity while limiting the damage in the event of failure. Risk is therefore contained within what impact an organization is prepared to withstand to gain the necessary knowledge to move forward.

Sensing: Working with the system changes the system, therefore watching for old and new patterns in the system and making meaning of the new patterns is a critical activity. Reflection on practice involves questioning – what is happening? Are we going in the right direction? What haven’t we done yet? Have we done enough to progress the design options to release “into the wild”? Have we identified relevant drivers, influences and weak signals?

Storytelling: Experiential processes generate stories and micro-narratives as a natural part of human activity. The more these stories are collected and shared, the more sensemaking, learning and understanding is released into the system. Stories can encompass all dimensions of change – especially those that signify patterns that may be adverse for the change process. We also build better relationships through shared stories, and when the transformation enters difficult phases, these story-supported relationships may make the difference in progressing to a better system state.

Adapting: Promoters of transformation take responsibility for the change outcome in the system – including unforeseen, emergent outcomes that may run counter to the intent of the transformation. So, as new patterns are identified and understood, practices need to be adapted and re-oriented as ongoing responsiveness. If something isn’t working or more information is needed, or the context changes as its being worked on, then re-activate other actions. It may be that other Design Cycle Elemental Patterns may need re-visiting: the system maps were not useful; more experimentation is needed; the participation was limited; hidden structures were not surfaced and so on.

Releasing: The transformation work goes live: it is released into the wild and sparks the nominal commencement of the next Phase. Participants, stakeholders, and the external system will launch their own adaptive strategies, creating new patterns in response. Once an initiative is released into the wild, the system plays with it, and the myriad pro-goal and anti-goal actions play out, and over time new patterns will emerge. The proponents of change in the organisation should not only watch for new emerging patterns that might need amplifying or dampening, but they should also empower all participants to identify and narrate how the changes play out in their parts of the organization, so that reflective learning processes can be applied.

Diffusing: A transformation design leaving one Phase Pattern Element and entering the next Phase Pattern Element must be diffused throughout the organisation to ensure the process continues. Diffusing brings in many factors, such as education, storytelling, reflection and sensemaking, and must be applied with awareness of actively engaging people in all parts of the organisation.

Impacting: Every action has an impact – and practitioners and participants alike need to understand the impact of actions. The design leaving each phase will create a new set of impacts, both obvious and hidden. Actively identifying impacts of emerging patterns is a critical aspect of the Bridging Pattern in preparation of the next phase of design. The second, third and fourth order impacts of the Activation Phase Design Cycle commence their emergence, too (see Figure X Orders of Impact above), so practitioners should watch for their emergence while celebrating the positive first order impacts.

Reflecting: This is the pause before initiating the next Phase – the taking in of a collective deep breath to reflect on the story so far, the making of meaning and the learning for the participants and practitioners across the organisation. Reflecting at this point will in large part influence what is taken forward, to extend, to build on, to adapt and to experiment with.

Atlas Navigation

Go to the Elemental Patterns within the Design Cycles Pattern:

Orienting Leading Understanding Mapping Framing Graining Scanning Surfacing Modelling Participating Specialising Advocating Creating Experimenting Sensing Storytelling Adapting Releasing Diffusing Impacting Reflecting

Go to the Pathways Pattern within the Transforming Patterns Cluster

Go to the Phase Pattern within the Transforming Patterns Cluster

Version

Version 1.0 - 2 Jun 2024

Version 2.1 - 23 May 2025

Version 2.2 - 15 July 2025

Papanek, V. (1972). Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change. 2nd Edition. London: Thames and Hudson.